Art Roman Villa on a Hill floorplan sketch layout blueprint

The domus was more than a residence, it was also a statement of social and political power.

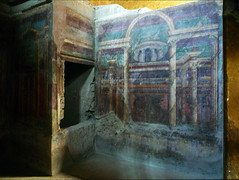

Peristyle, Casa della Venere in Conchiglia, Pompeii (Photo: F. Tronchin/Warren, BY-NC-ND two.0)

Introduction

Understanding the architecture of the Roman house requires more than simply appreciating the names of the various parts of the structure, as the house itself was an important part of the dynamics of daily life and the socio-economy of the Roman world. The house type referred to as the domus (Latin for "house") is taken to hateful a construction designed for either a nuclear or extended family and located in a city or town. The domus as a general architectural type is long-lived in the Roman world, although some development of the architectural form does occur. While the sites of Pompeii and Herculaneum provide the best surviving testify for domus architecture, this typology was widespread in the Roman world.

Layout

While there is not a "standard" domus, information technology is possible to hash out the main features of a generic example, keeping in mind that variation is present in every manifest instance of this type of building. The ancient architectural author Vitruvius provides a wealth of information on the potential configurations of domus compages, in particular the main room of the domus that was known as the atrium (no. 3 in the diagram above).

In the classic layout of the Roman domus , the atrium served equally the focus of the entire house plan. As the primary room in the public part of the house ( pars urbana ), the atrium was the heart of the house's social and political life. The male head-of-household ( paterfamilias ) would receive his clients on business days in the atrium, in which case it functioned equally a sort of waiting room for concern appointments. Those clients would enter the atrium from the fauces (no. 1 in the diagram to a higher place), a narrow entry passageway that communicated with the street. That doorway would be watched, in wealthier houses, by a doorman ( ianitor ). Given that the atrium was a room where invited guests and clients would wait and spend time, it was as well the room on which the house possessor would lavish attention and funds in gild to make sure the room was well appointed with decorations. The corner of the room might sport the household shrine ( lararium ) and the funeral masks of the family'due south expressionless ancestors might be kept in small-scale cabinets in the atrium. Communicating with the atrium might be bed chambers ( cubicula —no. 8 in the diagram above), side rooms or wings ( alae —no. 7 in the diagram above), and the office of the paterfamilias , known every bit the tablinum (no. 5 in the diagram higher up). The tablinum , often at the rear of the atrium, is usually a square sleeping accommodation that would have been furnished with the paraphernalia of the paterfamilias and his business interests. This could include a writing table likewise as examples of potent boxes as are evident in some contexts in Pompeii.

Types of atria

The organization of the atrium could take a number of possible configurations, equally detailed by Vitruvius ( De architectura 6.3). Amid these typologies were the Tuscan atrium ( atrium Tuscanicum ), the tetrastyle atrium ( atrium tetrastylum ), and the Corinthian atrium ( atrium Corinthium ). The Tuscan form had no columns, which required that rafters carry the weight of the ceiling. Both the Tetrastyle and the Corinthian types had columns at the eye; Corinthian atria generally had more columns that were likewise taller.

All three of these typologies sported a key aperture in the roof ( compluvium ) and a corresponding pool ( impluvium —no. 4 in the diagram in a higher place) set in the floor. The compluvium immune lite, fresh air, and rain to enter the atrium; the impluvium was necessary to capture whatever rainwater and channel it to an underground cistern. The water could then be used for household purposes.

Beyond the atrium and tablinum lay the more individual office ( pars rustica ) of the house that was often centered effectually an open-air courtyard known as the peristyle (no. 11 in the diagram higher up). The pars rustica would generally be off limits to business clients and served as the focus of the family unit life of the house. The central portion of the peristyle would be open to the heaven and could exist the site of a decorative garden, fountains, artwork, or a functional kitchen garden (or a combination of these elements). The size and organization of the peristyle varies quite a bit depending on the size of the house itself.

Communicating with the peristyle would be functional rooms like the kitchen ( culina —no. nine in the diagram above), bedrooms ( cubicula —no. 8 in the diagram above), slave quarters, latrines and baths in some cases, and the all of import dining room ( triclinium —no. 6 in the diagram above). The triclinium would be the room used for elaborate dinner parties to which guests would be invited. The dinner party involved much more than drinking and eating, however, as entertainment, discussion, and philosophical dialogues were often on the menu for the evening. Those invited to the dinner party would exist the close friends, family, and assembly of the paterfamilias . The triclinium would oftentimes be elaborately decorated with wall paintings and portable artworks. The guests at the dinner party were arranged co-ordinate to a specific formula that gave privileged places to those of higher rank.

Chronology and evolution

No architectural course is e'er static, and the domus is no exception to this rule. Architectural forms develop and change over time, adapting and reacting to changing needs, community, and functions. The chronology of domus compages is contentious, especially the give-and-take nigh the origins and early influences of the course.

Boosted resources:

Jean-Pierre Adam, Roman Building: Materials and Techniques , trans. Anthony Mathews (Bloomington IN: Indiana University Press, 1994).

Penelope M. Allison, "The Relationship between Wall-decoration and Room-blazon in Pompeian Houses: A Case Report of the Casa della Caccia Antica," Journal of Roman Archaeology 5 (1992), pp. 235-49.

Penelope M. Allison, Pompeian Households. An Analysis of the Material Culture (Los Angeles: Cotsen Plant of Archæology, University of California, Los Angeles, 2004). ( online companion )

Bettina Bergmann, "The Roman Business firm every bit Retentivity Theater: The Firm of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii," The Art Bulletin 76.2 (1994) 225-256.

C. F. M. Bruun, "Missing Houses: Some Neglected domus and Other Abodes in Rome," Arctos 32 (1998), pp. 87-108.

John R. Clarke, The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.-A.D. 250: ritual, infinite, and decoration (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991).

A. Due east. Cooley and M.G.L. Cooley, Pompeii and Herculaneum: a sourcebook, second ed. (London and New York: Routledge, 2014).

Peter Connolly, Pompeii (Oxford: Oxford Academy Press, 1990).

Kate Cooper, "Closely Watched Households: Visibility, Exposure and Private Ability in the Roman Domus," By & Present 197 (2007), pp. three-33.

Eugene Dwyer, "The Pompeian Atrium House in Theory and Practise," in E.K. Gazda, ed., Roman Art in the Private Sphere: New Perspectives on the Architecture and Decor of the Domus, Villa, and Insula (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991), pp. 25-48.

Carol Mattusch, Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Civilization around the Bay of Naples (Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2008.)

August Mau, Pompeii: its life and art (Washington D.C.: McGrath, 1973).

D. Mazzoleni, U. Pappalardo, and L. Romano, Domus: Wall Painting in the Roman House (Los Angeles: J Paul Getty Museum, 2005).

Alexander M. McKay, Houses, Villas, and Palaces in the Roman Globe (Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press,1975).

G.P.R. Métraux, "Ancient Housing: Oikos and Domus in Greece and Rome," Journal of the Social club of Architectural Historians 58 (1999), pp. 392-405.

Salvatore Nappo, Pompeii: a guide to the ancient metropolis (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1998).

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, "The development of the Campanian firm," in J.J. Dobbins and P.W. Foss, eds., The World of Pompeii (London and New York: Routledge, 2007) 279-91.

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, "Rethinking the Roman Atrium House," in R. Laurence and A. Wallace-Hadrill, eds., Domestic Space in the Roman Globe: Pompeii and Beyond (Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, 1997).

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, "The Social Construction of the Roman Firm," Papers of the British School at Rome 56 (1988), pp. 43–97.

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Houses and Society in Pompeii and Herculaneum (Princeton: Princeton Academy Press, 1996).

Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Herculaneum: Past and Future (London : Frances Lincoln Limited, 2011).

Timothy Peter Wiseman, "Conspicui postes tectaque digna deo: The Public Image of Aristocratic Houses in the Late Republic and Early on Empire," in L'Urbs: Espace urbain et histoire (1er siècle av. J.C.-IIIe siècle ap. J.C.) (Rome: Ecole Française de Rome, 1987) 393-413.

Paul Zanker, Pompeii: Public and Individual Life , trans. D. Fifty. Schneider (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998).

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

More Smarthistory images…

Source: https://smarthistory.org/roman-domestic-architecture-domus/

0 Response to "Art Roman Villa on a Hill floorplan sketch layout blueprint"

Post a Comment